Balantidium coli is the only ciliated protozoan and the largest protozoan parasite that routinely infects humans. The parasite causes a zoonotic disease (Balantidiasis), which occurs throughout the world, but the prevalence of human infection is not known. It was first described by Malmsten in 1857 in the feces of dysenteric patients. It is endemic in countries like Japan, New Guinea, Micronesia, the Seychelles Islands, Thailand, South Africa, Central and South America, and Europe. Sporadic epidemics have been recorded in institutionalized populations. Transmission is fecal-oral, from where the parasite migrates to the large intestine, causing amoebic diarrhea or frank dysentery with abdominal colic, tenesmus, and nausea and vomiting, occasionally leading to fatalities. It has many reservoir hosts, including both domestic and wild mammals (non-human primates, guinea pigs, horses, cattle, pigs, wild boars, and even rats). Diagnosis is established by demonstration of the parasite in feces. While motile trophozoites occur in diarrheal feces, cysts are found in formed stools. Treatment with tetracycline 500 mg every six hours for 10 days is successful. Metronidazole and nitroimidazole have also been reported to be useful. Prophylaxis consists of avoiding contamination of food and drink with human or animal feces.

In this article, you’ll be able to answer the following questions:

- What is Balantidiasis?

- What are the Signs, symptoms, causes and Treatment of Balantidiasis?

- Life cycle of Balantidium coli

- What is the laboratory diagnosis of Balantidium coli?

- Is Balantidium coli a zoonotic disease?

- What is the infective stage of Balantidium coli?

Taxonomic Classification of Balantidium coli:

- Kingdom: Protista

- Phylum: Ciliophora

- Class: Ciliata

- Order: Balantidiales

- Family: Balantidiidae

- Genus: Balantidium

- Species: Balantidium coli

Morphology

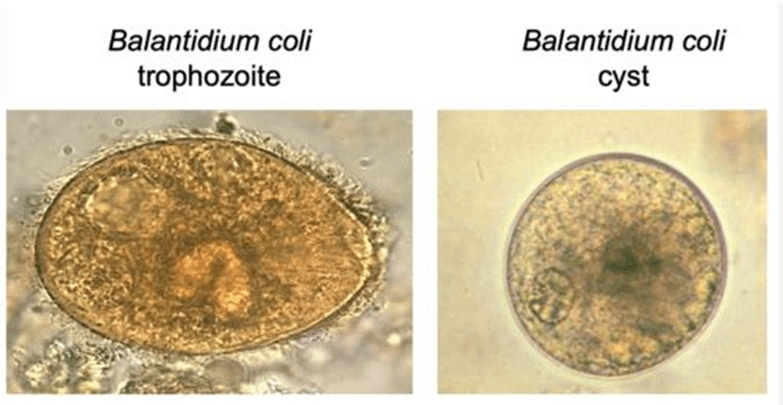

Trophozoites

- Balantidium coli is rather large and peripherally covered on the entire circumference of the cell by short cilia. It typically exhibits rotary, boring motility.

- Trophozoite stages vary in size from 30 to 120 μm by 30 to 80 μm. Some may reach 90 to 120 μm by 60 to 80 μm. It is tapered at the anterior portion with an attached cytostome. With two visible nuclei (a large kidney bean-shaped macronucleus and a micronucleus).

- The micronucleus is often not readily visible, even in stained preparations. The macronucleus may often appear as a hyaline mass, especially in unstained preparations.

- The trophozoites also have two contractile vacuoles, which are located in the granular cytoplasm, although sometimes only one is readily visible. The cytoplasm may also contain food vacuoles, which may contain ingested microbes (bacteria).

- Another important feature of the trophozoite is the presence of a small cytostome and a layer of cilia surrounding the organism as a means of locomotion.

Cyst

- The cyst form is elliptical in shape, measuring 45–65 μm, with visible food vacuoles seen in the cytoplasm. It also has a small opening at the posterior used for waste elimination.

- It also contains macro and micronuclei, which are usually not visible in wet or permanent preparations.

- One or more contractile vacuoles may be visible, especially in young, unstained cysts.

- The cyst has a double protective wall with cilia, though mature cysts tend to lose their cilia.

- Encystation occurs as the trophozoite passes down the colon. It also occurs when the trophozoite is evacuated from the stool. Here, the cell rounds up, secreting a tough cyst wall around it, and remains viable in feces for a day or two.

Life Cycle of Balantidium coli

- The life cycle involves two stages: the trophozoite and the cyst, with the trophozoite being the invasive stage.

- Balantidium coli resided in the tissues of the large intestine. It is advisable to clinically distinguish Balantidium coli from Entamoeba histolytica, which share the same habitat. The difference is that the trophozoites of B. coli ingest living cells and cause ulcerations at the site of infection. Entamoeba histolytica cysts are smaller and mostly seen in loose stool, while those of Balantidium coli cysts are larger in diameter and usually seen in formed stools.

- Infection begins with the ingestion of the cyst, and this can be through the consumption of contaminated food or water.

- The trophozoite excysts in the small intestine and relocates to the large intestine.

- The preferred site of infection is the epithelium of the transverse and descending colon, and the parasite is usually limited to the bowel.

- Division occurs by simple binary fission within the host, while in the culture medium, the parasite behaves like all other free-living ciliates.

- The trophozoites cause extensive destruction of the surrounding tissue, and during prolonged infection, some trophozoites can enter the lumen of the colon, where they secrete hyaline, an impervious acellular layer, resulting in the formation of the cyst.

- The cyst exits from the host mixed with fecal mass and immediately becomes infectious without the requirement for an intermediate host, therefore favoring direct human-to-human transmission.

Pigs are presumed reservoirs in most ecological settings since infection is more common where pigs live in close association with human habitats. Guinea pigs are also thought to harbor the parasite as a commensal and have been identified as the source of some human infections.

Pathogenicity

- Balantidium coli can survive in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. It uses carbohydrates as a source of energy.

- Hyaluronidase is an enzyme found in trophozoites that facilitates the lysis of intestinal epithelial cells, disrupting the mucosal epithelial cells.

- Proteases are enzymes of lysosomal origin released by food vacuoles involved in the process of digestion of cell debris that enters through the peristome (a mouth-like opening) located at the narrowed end of the trophozoite.

- Infection is acquired from pigs and other animal reservoirs or from human carriers.

- The infective form is the cyst, which is ingested in contaminated food or drink, and excystment takes place in the small intestine, liberating trophozoites that reach the large intestine, where they feed and multiply as lumen commensals.

Clinical Disease (Signs, symptoms, causes)

- Infection is very often confined to the lumen and is asymptomatic.

- As for clinical disease, it only results when the trophozoites burrow into the intestinal mucosa, set up colonies, and initiate an inflammatory reaction leading to mucosal ulcers and submucosal abscesses that resemble the lesions in amoebiasis.

- Balantidiasis clinically ressembles amoebiasis with symptoms such as diarrhea or frank dysentery with abdominal colic, tenesmus, asthenia, nausea, and vomiting.

- Occasionally, there may be intestinal perforation with peritonitis and, rarely, involvement of the genital and urinary tracts.

- Immunocompromised individuals due to malnutrition, HIV infection, or other causes may develop an invasive disease with organisms invading the lungs, urinary tract, liver, and heart.

Diagnosis

- Definitive diagnosis is the identification of the organism (cyst or trophozoite) by microscopy in a stool sample or from a stained section of tissue obtained from a biopsy of an ulcer identified by colonoscopy.

- Trophozoites can also be found in freshly obtained watery stools, while the cyst stage is only present in formed stools.

- It can also be recovered from culture medium, though it is not routinely used for diagnosis, making stool microscopy the only diagnostic test.

Treatment

- Tetracycline 500 mg every six hours, for 10 days (Tetracycline is contraindicated in pregnant patients and in children less than eight years old).

- Metronidazole

- Iodoquinol

- Paromomycin

- Nitazoxanide

- Chloroquine

- Surgery (bowel resection) is sometimes necessary in severe cases of dysentery.

Prevention and Control

- Water, hygiene, and sanitation are important for controlling the spread of B. coli.

- Prophylaxis consists of avoiding contamination of food and drink with human or animal feces.

- The usual concentration of chlorine used to purify water is not adequate to destroy the cyst stage of Balantidium coli.

- Domestic pigs would need to be restricted from releasing infective cysts into waters that would end up in municipal water supplies to interrupt transmission.

- Considering that a high percentage of swine in many parts of the world are infected with Balantidium coli. When pigs share the same space with humans, as is the case in many parts of the less-developed world, the risk of infection is high. Therefore, avoid close contact with these animals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Balantidium coli is a parasitic protozoan that primarily infects the large intestines of humans and animals. It is transmitted through the ingestion of contaminated food or water and can cause a range of gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nausea. While infections are relatively rare, proper hygiene and sanitation measures can help prevent the spread of this parasite. Some may argue that the impact of Balantidium coli on human health is negligible due to the rarity of infections and the effectiveness of preventive measures such as hygiene and sanitation. However, even though infections may be rare and preventive measures effective, it is still important to consider the potential severity of the symptoms caused by Balantidium coli, as they can greatly impact an individual’s quality of life and well-being.

Workshop

- One of the easiest ways of identifying Balantidium coli trophozoites is by collecting stool samples from a pig ranch or hog farm and observing them under the microscope (10–40 objective).

- They are usually very motile, and positive results indicate possible contamination and a threat to the surrounding environment.

References

- Nakauchi, K., The prevalence of Balantidium coli infection in fifty-six mammalian species. The Journal of veterinary medical science / the Japanese Society of Veterinary Science 1999, 61 (1), 63-5

- Castro, J.; Vazquez-Iglesias, J. L.; Arnal-Monreal, F., Dysentery caused by Balantidium coli– report of two cases. Endoscopy 1983, 15 (4), 272-4.

- Solaymani-Mohammadi, S.; Rezaian, M.; Hooshyar, H.; Mowlavi, G. R.; Babaei, Z.; Anwar, M. A., Intestinal protozoa in wild boars (Sus scrofa) in western Iran. J Wildl Dis 2004, 40 (4), 801-3.

- Esteban, J. G.; Aguirre, C.; Angles, R.; Ash, L. R.; Mas-Coma, S., Balantidiasis in Aymara children from the northern Bolivian Altiplano. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998, 59 (6), 922-7.

- Balantidium coli, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balantidium_coli

1 Comment

Pingback: Entamoeba histolytica: Epidemiology and Pathology Unveiled for Better Diagnosis and Treatment - medlabnotes.com