Parvovirus B19 is a small but powerful virus that can cause significant health concerns, especially in certain groups. Understanding what it is and how it affects you is crucial for recognizing its symptoms and knowing how to manage potential risks. This post will explore the virus’s transmission, symptoms, and the groups most at risk. By the end, you will have a clearer picture of Parvovirus B19 and what steps you can take to protect yourself and your loved ones.

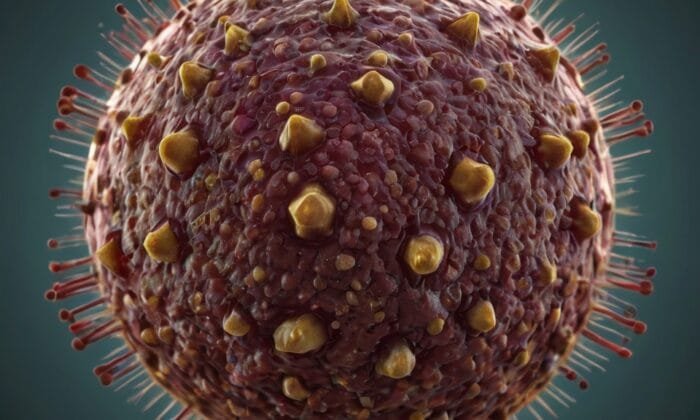

Parvovirus B19 is a very small DNA virus that is the only known human parvovirus. It is a member of the erythrovirus genus in the Parvoviridae family. Although parvoviruses are present in many other animal species, such as dogs, they do not infect humans.

The virus multiplies in erythroid progenitor cells, which it infects by attaching itself to the P antigen, one of the blood type antigens produced on the cell surface that serves as a viral receptor.

Epidemiology of Parvovirus B19

Method of transmission

The virus begins its replication in the respiratory mucosa and spreads across the respiratory system by droplet transmission as opposed to aerosol transmission. In vulnerable home contacts, the attack rate is almost 50%, but it is significantly lower in a community context.

Since there is a brief window of viraemia before a rash develops, blood transfusions during the prodromal phase have occasionally resulted in transmissions.

Prevalence of Parvovirus B19

Parvoviruses are common everywhere in the world. Half of young people have signs of a prior parvovirus infection. Parvovirus is a childhood infection, and the incidence of antibodies increases with age.

Incubation period

Is about 12–18 days.

Infectious period

Patients are not contagious after the rash begins, but the prodromal phase, which lasts for two days, is the time of greatest infectivity.

Individuals at risk of Parvovirus B19

- Individuals with hemolytic anemia

- Immunocompromised patients

- Expectant mothers

Signs and symptoms

Erythema infectiosum

Another name for this is the fifth disease. Approximately half of infections, particularly in young children, have no symptoms. A symptomatic infection is typified by an immune-mediated, fine maculopapular rash that develops after a few days of fever, malaise, and upper respiratory symptoms. The condition is known as “slapped cheek syndrome” because the youngster usually has a rash on their cheeks (malareminences), giving the impression that they have been smacked on both cheeks. There may be a widespread rash over the body and limbs; this is often quite temporary, but reports of rashes lasting up to two or three weeks have been made. Up to 30–50% of individuals with parvovirus infection experience joint pain, or arthralgia, which may be their only presenting symptom. These often affect the larger joints, but they can also affect the smaller joints, and they can last for several weeks. Sometimes an infection results in true rheumatoid factor positive arthritis.

Complications of Erythema infectiosum

A brief decrease in red blood cells is the only effect of a transitory infection of the erythroid precursor cells, and in healthy, immunocompetent children and adults, this does not show up as anemia. However, problems arise because of severe anemia with aplastic symptoms in the following at-risk categories.

Infections in pregnancy

Up to 30% of cases may result in fetal transmission, yet it is not linked to congenital malformations or birth abnormalities. If an infection develops before 20 weeks of pregnancy, 7–10% of infected women have fetal loss. In 2-3% of infected women, hydrops fetalis is the most serious fetal consequence. Fetal oedema and ascites from severe fetal anemia are the cause of the disorder, which is treated with intrauterine blood transfusions till the fetus recovers in a few weeks.

Fetal infection is possible after 20 weeks of gestation, however it does not always result in a bad outcome for the fetus. Additionally, evidence points to a higher risk of fetal infection transfer in cases of silent illness during pregnancy than in cases of symptomatic infection, with the former suggesting a compromised host immune response and ineffective virus clearance.

Infection in immunocompromised patients

May cause the immune system to fail in its attempt to eradicate the virus, leading to a chronic parvovirus infection. The patient experiences uncontrollably persistent aplastic anemia.

Infection in patients with haemolytic anaemia

Red blood cell death, together with a precipitous decline in red blood cells and hemoglobin, are the main causes of aplastic crisis. At the onset of the aplastic crisis, the patient is typically viraemic. The patient recovers from the aplastic crisis with a reticulocytic response once the immunological response has been built. These patients typically don’t get a rash.

Laboratory diagnosis

| Clinical indication | Specimen | Test | Significance | Essential information for the laboratory |

| Diagnosis of acute parvovirus infection | Serum | Parvovirus IgM | Positive result denotes recent infection. | Clinical symptoms, date of onset, any history of any risk factor e.g. pregnancy, immunocompromised or aplastic crisis. |

| Diagnosis of acute infection in the immunocompromised and in patients with aplastic crisis | Serum | Parvovirus DNA PCR | Positive result indicates recent or chronic infection. Specific IgM may be negative in immuno-compromised patients due to poor immune response. | Clinical details and symptoms with risk factors if any, date of onset. |

| Diagnosis of fetal infection | Cord blood by cordocentesis | Parvovirus DNA PCR and IgM if fetus is more than 20 weeks | Positive IgM and/or PCR indicates fetal infection. | Gestational age of the fetus, presence of hydrops. |

| Check immune status | Serum | Parvovirus IgG by EIA | A positive IgG in the absence of parvovirus-specific IgM indicates past infection | History of and date of recent contact if any, risk factors for infection. |

Management of Parvovirus B19

Treatment of Parvovirus B19

Immunocompetent patients get supportive care rather than specialized care.

- In individuals with aplastic crises and immunocompromised people. The purpose of blood transfusions is to raise and sustain hemoglobin levels. It has been demonstrated that intravenous IgG therapy is useful in treating infections.

- Fetal hydropsis. Regular ultrasounds should be used to monitor the pregnancy, and in cases of hydrops fetalis, intrauterine blood transfusions should be used to treat fetal anemia. Once the fetus is able to control the infection, the hydrops cures on its own. Such pregnancies successfully go to term with a normal outcome, and there is no indication that the fetus will suffer long-term harm.

- Maternity. If an acute parvovirus infection occurs in a pregnant woman, she should be referred to an obstetrician so that the pregnancy can be monitored closely and treated effectively in case hydrops fetalis occurs (see above).

Prophylaxis

There is no particular vaccination or prophylactic.

To establish immunity, pregnant women who come into contact with a known case of parvovirus B19 infection should undergo parvovirus IgG testing. Four weeks following contact, those who were confirmed to be vulnerable should undergo another test to be sure they haven’t contracted a subclinical infection—of which 50% of adults are susceptible.

Infection control

- When possible, patients should be kept apart while using respiratory protective measures.

- Patients with hemolytic anemia in aplastic crises typically have a long duration and high infectivity without developing a rash.

- Patients who are at risk of problems from parvovirus should be advised to avoid infection.

- Individuals who have an infection should also be counseled against interacting with immunocompromised or hemolytic anemia patients, as well as pregnant women.

- Patients at risk of parvovirus infection consequences should be evaluated for immunity, monitored if they are vulnerable, and treated properly if symptoms appear.

- Healthcare professionals who work with patients who are at risk of contracting parvovirus B19 should remain off the job for seven days to three weeks following exposure to allow for incubation. This time frame applies whether the person was exposed at work or at home.

Source: Clinical and Diagnostic Virology, GOURA KUDESIA and TIM WREGHITT. Parvovirus B19 P. 90|

1 Comment