Hello everyone! As a lecturer with a background in medical laboratory science, I often encounter questions about Giardia lamblia, a common yet intriguing intestinal parasite. Whether you’re a student, a lab professional, or simply curious about parasitology, understanding Giardia is vital for accurate diagnosis, treatment, and control. Let’s explore this parasite thoroughly—covering its morphology, lifecycle, clinical relevance, diagnosis, epidemiology, and prevention.

What is Giardia lamblia?

Giardia lamblia (formerly known as Giardia intestinalis or Giardia duodenalis) is a flagellated protozoan parasite that infects the human and animal small intestine. It is a leading cause of parasitic gastrointestinal disease globally, with Infection caused by Giardia leading to giardiasis, characterized primarily as diarrhea and malabsorption (Fasih et al., 2017).

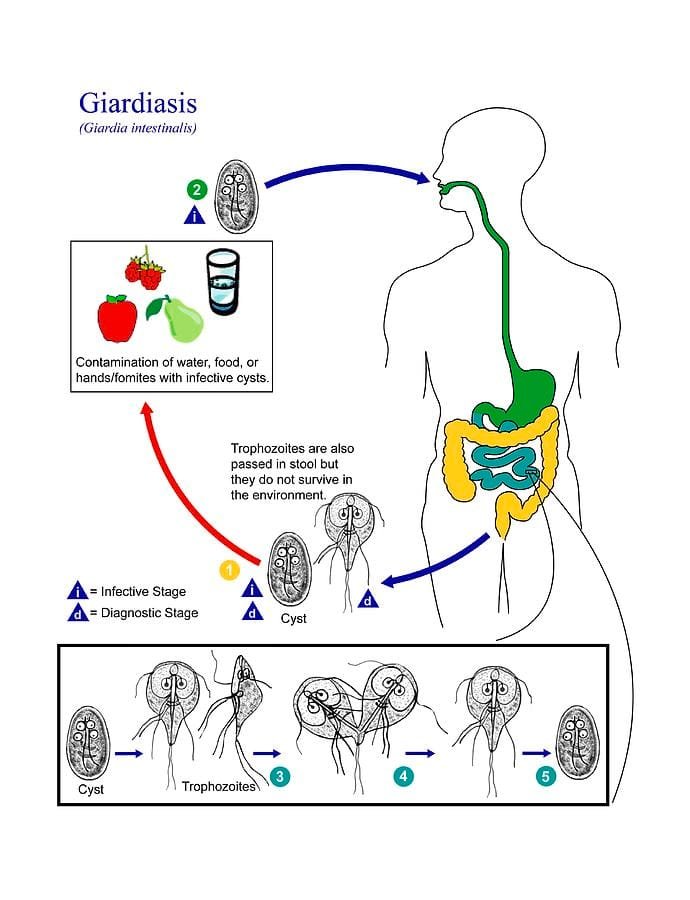

Key point: Giardia exists in two stages:

- Trophozoite: The motile, feeding form within the host.

- Cyst: The environmentally resistant, infective form excreted in feces.

Morphology and Identification

Knowing the morphology of Giardia is important because it is useful in the laboratory for species identification, primarily by use of microscopy.

Trophozoite

- Shape: Pear or teardrop shape.

- Size: About 12-15 μm in length and 7-10 μm in width.

Characteristics:

- 2 nuclei which resemble eyes (called the “face” of Giardia).

- 4 pairs of flagella for locomotion.

- Ventral adhesive disc: For adherence to intestinal mucosa.

- Cytoplasm: Granular appearance.

Cyst

- Shape: Elliptical or oval.

- Size: Approximately 8-12 μm.

Identification Features:

- Nuclei: Mature cysts will show four nuclei that appear as small dots.

- Cyst wall: Thick, smooth, protective.

- Number of nuclei: Important to determine stage; mature cysts will have four nuclei.

The life cycle of Giardia lamblia

Understanding the life cycle assists in understanding transmission and control. Here is a simplified model of the Giardia life cycle:

- Ingestion: Humans will become infected through ingestion of cysts in contaminated water, food, or fecal-oral contact.

- Excystation: The excystation phase occurs in the small intestine, and the cysts will release trophozoites.

- Colonization: Normally triggered by a change in pH or temperature, the trophozoites will attach to the intestinal mucosa using the ventral disc. The trophozoites will then replicate by binary fission, and the colonization will result in symptoms.

- Encystation: Some of the trophozoites will change to cysts in the intestine.

- Excretion: Cysts are shed in the environment through feces.

- Survival in the environment: Cysts can survive in water and warm moist soil for several weeks, increasing transmission potential.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Signs

Giardia primarily causes intestinal dysfunction through mechanisms involving mucosal adherence and mucosal injury, with resultant malabsorption.

Common clinical signs include:

- Diarrhea, often greasy and foul-smelling

- Cramping abdominal pain

- Distention with abdominal tenderness and flatulence

- Nausea

- Weight loss and malnourishment, especially in young children

- Fatigue

In some cases, especially in immunocompromised hosts, signs and symptoms may be prolonged or atypical.

Epidemiology of Giardia lamblia

Giardia is a ubiquitous parasite that occurs globally, especially in poorly sanitized areas.

Epidemiological facts:

- Prevalence: Estimated at 2-7% in the developed world and as high as 30% in developing countries (Fasih et al., 2017)

- Transmission: Commonly through the ingestion of cysts in contaminated water, food, or via person-to-person contact.

- Risk factors: Poor sanitation, water that is contaminated, daycare attendance, travel to endemic areas, and close contact with infected people

- Reservoirs: Domestic and wild animals namely dogs and cats harbor and transmit Giardia.

Epidemiological data has provided invaluable information regarding the impact of water sanitation and hygienic practices and improving the public health of giardiasis.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Reliable identification of Giardia is necessary for treatment.

Microscopic Examination

- Microscopy of stool: The gold standard is detection by the visualization of cysts or trophozoites.

- Direct wet mount preparation with saline (or iodine) stain.

- Concentration techniques (e.g., formalin-ethyl acetate) can become beneficial by increasing sensitivity.

- Trophozoites should be observed in the wet mount only from fresh stool; if found in formed stool, they would be more than one or two (trophozoites are fragile); cysts are stable.

Antigen Detection

- Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA): commercially-available kits for detecting Giardia antigens in stool specimens, high sensitivity (~90%) and specificity (~95%) (Fasih et al., 2017).

Molecular Over-Detection Techniques

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction: PCR is more sensitive and specific; recommended for research purposes, complex cases.

Practical applications:

- To improve the diagnosis of Giardia, collect three or more stool samples on consecutive days.

- Use only freshly-passed stool, if detecting for trophozoites.

- Concentration techniques; staining techniques allow for better visualization of trophozoites

Prevention and Control

To prevent the spread of giardiasis, it is important to break the transmission cycle:

- Consume safe, treated water; avoid drinking untreated surface water.

- Good personal hygiene; wash hands after defecation.

- Wash all food and cook food.

- Take steps to ensure sanitation within communities and institutions.

- Educate at-risk populations about transmission routes.

In endemic countries, mass drug administration could be warranted.

Summary

Giardia lamblia is a fairly common protozoan parasite of importance to human health, especially in low/limited-resource contexts. Its morphology and lifecycle and clinical presentations make it an important organism that all medical laboratory technologists should know about.

Important Points:

- Identifying the trophozoite and cyst forms of Giardia.

- Knowing how the lifecycle works to control development of illness and diagnose illness properly.

- Knowing which laboratory methods give the best results in terms of detection and demonstration.

- Prevention should be emphasized where possible through hygiene and sanitation.

References

- Fasih, M., Abbas, N., & Saeed, M. (2017). Giardia lamblia – An overview. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 33(1), 1–6.

- García, L. (2018). Diagnostic Medical Parasitology. ASM Press.

- Ryan, U., & Cacciò, S. M. (2016). Zoonotic Giardia and Cryptosporidium in the environment. Trends in Parasitology, 32(10), 839–852.

- WHO. (2017). Drinking-water fact sheet. World Health Organization.

Want To Know More?

Please leave a question below, or share what you have experienced. Would you like to see some actual laboratory-type procedures, or case study examples? Let me know! For additional detail, or the latest updates in the field, please subscribe or follow the parasitology series companion to this document.