Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite known for causing amoebiasis, a disease that affects the intestines and can lead to severe symptoms such as dysentery and liver abscesses. This parasite is commonly found in areas with poor sanitation and hygiene practices, making it a significant public health concern in developing countries. Entamoeba histolytica is transmitted through contaminated food and water sources, making prevention strategies crucial to reducing the spread of the parasite. Early detection and treatment are essential in managing amoebiasis and preventing complications. The symptoms of amoebiasis can vary from mild to severe, with some cases being asymptomatic. Proper hygiene, clean water sources, and proper sanitation practices are key to preventing the transmission of Entamoeba histolytica. In addition to preventive measures, individuals should also seek medical attention if they experience symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can help prevent the progression of the infection and potential complications associated with amoebiasis. If left untreated, amoebiasis can lead to severe complications such as liver abscesses and intestinal perforation. Therefore, it is important to consult a healthcare provider for proper evaluation and management if symptoms persist.

Through this article, you’ll be able to answer the following questions:

- What is the disease caused by Entamoeba histolytica?

- How is Entamoeba histolytica transmitted?

- What is the treatment for Entamoeba histolytica?

- What are 5 characteristics of Entamoeba histolytica?

- What is the common name for Entamoeba histolytica?

- How to prevent Entamoeba histolytica?

- What organ is most affected by Entamoeba histolytica?

- What are three symptoms of amebiasis?

- What medication is used to treat amoeba?

Classification

| PHYLUM | SUBPHYLUM | EXAMPLES OF SPECIES |

| Amoebozoa | Sarcodina | Entamoeba histolytica |

Morphology

Trophozoites

- E. histolytica trophozoites have a size range of 8-65 µm, with an average of 12-25 µm.

- Parasite names are often abbreviated to the first letter of the genus followed by the species name, e.g., E. histolytica for Entamoeba histolytica.

- The trophozoite moves rapidly and unidirectionally using finger-like hyaline pseudopods.

- The nucleus contains a karyosome, a small central mass of chromatin. Eccentric or fragmented karyosomal material is one example of a karyosome variant.

- The amebic parasite’s karyosome is surrounded by chromatin, known as peripheral chromatin. Peripheral chromatin is usually fine and evenly distributed around the nucleus in a perfect circle. Variations, such as uneven peripheral chromatin, can also be observed.

- While the appearance of the karyosome and peripheral chromatin may differ, most trophozoites share the following characteristics.

- When a preparation is stained, the nucleus that was previously invisible becomes visible.

- E. histolytica trophozoites have finely granular cytoplasm that resembles ground glass.

- E. histolytica is the only intestinal ameba that produces red blood cells (RBCs) in its cytoplasm, making it a diagnostic marker.

- The presence of bacteria, yeast, and debris in the cytoplasm is not diagnostic.

Cyst

- E. histolytica cysts range in size from 8 to 22 µm, with an average of 12 to 18 µm. The presence of a hyaline cyst wall aids in identification of this morphological form. Young cysts have unorganized chromatin that forms chromatoid bars, which contain condensed RNA material.

- Young cysts often show a diffuse glycogen mass, a cytoplasmic area without defined borders thought to store food. As the cyst matures, the glycogen mass disappears, indicating the use of stored food. Typically, one to four nuclei are present.

- These nuclei resemble trophozoite nuclei, but are typically smaller. Common nuclear variations include eccentric karyosomes, thin plaques of peripheral chromatin, and a crescent-shaped clump of peripheral chromatin on one side of the nucleus.

- The mature infective cyst has four nuclei. The cytoplasm remained fine and granular. The cyst stage does not contain RBCs, bacteria, yeast, or other debris.

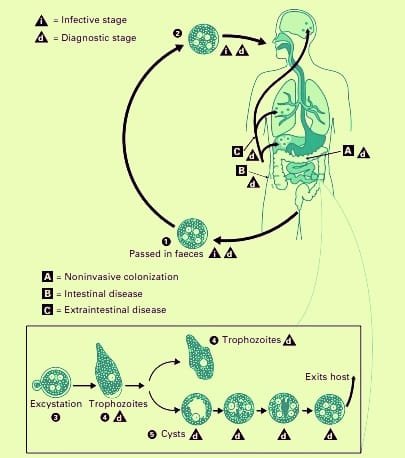

Life Cycle of E. histolytica

- The parasite infects by developed cysts seen in the feces of carriers and convalescents.

- The cysts may survive in damp environments for around 10 days.

- Ingestion of infected food or drink allows cysts to pass past the stomach and reach the small intestine without harm.

- When the surrounding medium turns alkaline. Trypsin damages the cyst wall in the gut, causing excystation.

- As the cytoplasm detaches from the cyst wall, amoeboid motions create a tear, allowing the quadrinucleate amoeba to emerge.

- This stage is known as the metacyst. The metacyst divides into eight nuclei, each with its own cytoplasm, resulting in eight tiny amoebae or metacystic trophozoites.

- Excystation in the small intestine leads to metacystic trophozoites being transported to the caecum rather than colonizing there.

- Metacystic trophozoites thrive in the caecal mucosa, settling within glandular crypts and undergoing binary fission. Some grow into precystic forms and cysts, which are then passed in feces to continue the cycle.Thus, the full life cycle can be completed in a single host.

- Infection with E. histolytica does not always result in illness. Typically, it feeds on colonic contents and mucus as a commensal within the large intestine, causing no harm.

- Individuals who have cysts in their feces may become asymptomatic carriers or passers.

- They maintain and disseminate illness throughout the population. In many cases, the illness may be eradicated naturally.

- Infections can sometimes lead to clinical illness. Latency and reactivation are hallmarks of amoebiasis.

Pathogenicity

The lumen-dwelling amoebae do not cause sickness. Only when they enter the digestive tissues do they cause illness. This occurs in only approximately 10% of instances of illness; the other 90% are asymptomatic. The causes affecting tissue invasion are not entirely known.

Not every strain of E.histolytica is harmful or invasive. In vitro, all strains may cling to host cells and cause proteolysis of host cell contents; however, only pathogenic strains can do so in vivo. Pathogenic (P) and nonpathogenic (NP) strains can be distinguished using several approaches, such as sensitivity to complement-mediated lysis, phagocytic activity, genetic markers, or monoclonal antibodies. Amoebic cysteine proteinase, which inactivates the complement component C3, is a key virulence factor for P strains. E.histolytica strains may be categorized into at least 22 zymodemes based on the electrophoretic mobility of six isoenzymes (acetylglucosaminidase, aldolase, hexokinase, NAD-diaphorase, peptidase, and phosphoglucomutase). Only nine of these are invasive (P), whereas the remainder are noninvasive (NP) commensals. The zymodemes have a geographical distribution. In endemic areas, NP zyodemes outnumber P zyodemes, which make up just 10% of the population.

Although morphologically identical, P and NP strains may represent different species: E.histolytica for P strains and E.dispar for NP strains. Trophozoites of E.dispar contain bacteria but no red blood cells.

Stress, starvation, drunkenness, corticosteroid medication, and immunodeficiency can all have an impact on infection outcomes. Colonic mucus glycoproteins interact with amoeba trophozoite surface receptors, preventing them from attaching to epithelial cells. Variations in the type and amount of intestinal mucus may thereby impact pathogenicity. The colon’s bacterial flora may also influence virulence.

Metacystic trophozoites penetrate columnar epithelial cells in Lieberkuhn crypts in the colon. Amoebae emit tissue lytic chemicals that injure the mucosal epithelium, and the trophozoite’s motility assist penetration. The amoeba penetrates the mucosa, forming distinct ulcers with a pinhead center and elevated margins. Sometimes the invasion is shallow and limited to the mucosal epithelium, resulting in erosion that may expand laterally. These heal on their own and have no negative consequences. Amoebae often colonize the submucosal layer, causing lytic necrosis and abscess formation. The abscess develops into an ulcer. Ulcers are concentrated in the colon, particularly in the caecum and sigmoido-rectal area. The mucosal membrane between ulcers remains healthy.

Ulcers first form on the mucosa as elevated nodules with pouting edges. They eventually break down, releasing brownish necrotic material containing a significant number of trophozoites. Amoebic ulcers often have a flask-shaped cross section, with a narrow mouth and neck and a broad, circular base. Multiple ulcers might combine to produce massive necrotic lesions with ragged or weakened margins and brownish slough. The ulcers do not often go deeper than the submucous layer, but amoebae disseminate laterally in the submucosa, resulting in significant undermining and patchy mucosal loss. Amoebae can be detected along the edges of the lesions and expanding into the surrounding healthy tissues. Ulcers can sometimes affect the colon’s muscular and serous coats, resulting in perforation and peritonitis. Blood vessel degradation can result in hemorrhage.

Deep ulcers can cause strictures, partial blockage, and thickening of the gut wall, but superficial lesions usually heal without leaving scars. Chronic ulcers can sometimes cause granulomatous growths on the intestinal wall. This amoebic granuloma or amoeboma might be mistaken for a cancerous tumor.

Amoebae invade the intestinal wall and go through the portal vein to the liver. While most do not lodge, a few do establish themselves in the hepatic lobules, causing lytic necrosis with little inflammation.

Hepatic invasion is widespread, with the right lobe being particularly afflicted. Leucocytic infiltration increases when lesions grow and necrosis persists. There is also an expansion of the liver. This stage is referred to as amoebic hepatitis.

One or more of the liver lesions may spread peripherally and develop into amoebic abscesses. Which can range in size from a few millimetres to many centimetres. The center of the abscess is filled with thick chocolate brown pus (‘anchovy sauce pus’), which is liquefied necrotic liver tissue. It is bacteriologically sterile and devoid of amoebas. A median zone of coarse stroma exists immediately surrounding the core necrotic region. The peripheral is almost normal liver tissue, with invading amoebae. Rapidly developing abscesses may only have liver tissue as a limiting capsule, while persistent lesions have a fibrous wall around them. Liver abscesses can be numerous or single, often found in the upper right lobe of the liver. Multiple lesions or pressure on the biliary system can cause jaundice. Untreated abscesses can spread to surrounding tissues and organs, including the lung, pleural cavity, pericardium, stomach, intestine, and inferior vena cava, as well as externally via the abdomen wall and skin.

Amoebiasis of the lung is often caused by an abscess rupturing through the diaphragm, rather than direct haematogenous dissemination from the colon without hepatic involvement. It is most commonly found in the lower right lung. Typically, a hepatobronchial fistula causes expectoration of chocolate colored sputum. Rarely, an amoebic empyema develops.

The involvement of distant organs occurs through haematogenous spread. Abscesses occur in the brain, spleen, adrenals, and kidneys.

Cutaneous amoebiasis spreads through the rectum, colostomy holes, and sinuses that drain liver abscesses. Extensive necrosis and sloughing occurs. Trophozoites can be seen in the lesions. It can also cause a venereal infection of the penis after anal intercourse.

Clinical Disease (Signs, symptoms, causes)

The incubation time is quite varied, ranging from four days to a year or more. The average duration is 1–4 months. The clinical course consists of extended latency, relapses, and intermissions.

Amoebiasis can affect different organs and inflict varying degrees of harm. Amoebiasis can occur in the intestine or outside the body.

Intestinal Amoebiasis

The clinical picture ranges from noninvasive carrier status to fulminant colitis.

Amoebic dysentery is a characteristic sign of intestinal amoebiasis. This condition may mimic bacillary dysentery, but may be distinguished by clinical and laboratory tests. Compared to bacillary dysentery, it often has a gradual start, less stomach discomfort, and is more localized.

The stools are large, foul-smelling, and brownish black, with blood-streaked mucous mixed with feces. Stools include clumped red blood cells that appear reddish brown. Cellular exudate is minimal. Charcot-Leyden crystals are frequently found.

E.histolytica trophozoites can be detected with ingested erythrocytes. Patients are typically afebrile and nontoxic. Fulminant colitis leads to ulceration and necrosis of the colon. The patient is both febrile and toxic.

Intestinal amoebiasis does not usually cause dysentery. Diarrhea and ambiguous abdominal symptoms, also known as “uncomfortable belly” or “growling abdomen,” are common. Chronic involvement of the caecum mimics appendicitis.

Extraintestinal Amoebiasis

Hepatic involvement is the most prevalent extraintestinal consequence of amoebiasis. Although trophozoites reach the liver in most episodes of amoebic dysentery, only a tiny percentage of them lodge and multiply there. Amoebic colitis can cause an enlarged, painful liver without any noticeable impairment in function or fever. Acute hepatic involvement, often known as amoebic hepatitis, can be caused by amoebae from an active colonic infection or toxic chemicals reaching the liver. Lysosomal enzymes and cytokines from inflammatory cells around trophozoites may induce liver injury, rather than the amoebae themselves. In 5-10% of individuals with intestinal amoebiasis, a liver abscess may develop. It is more prevalent in older males. The patient experiences heaviness, pain in the liver, and referred pain in the right shoulder. Fever and chills are prevalent, as is weight loss. Jaundice isn’t common.

Pleuropulmonary amoebiasis typically develops after a hepatic abscess spreads through the diaphragm, affecting the lower right lung. Abscesses can arise at any point on either lung due to haematogenous dissemination, but this happens very rarely. When an abscess drains into the bronchus, reddish brown pus is spat out.

Amoebic abscesses in the brain can be caused by haematogenous dissemination from amoebic lesions in the colon or other sites. It causes significant brain tissue damage and is deadly. Abscesses in other organs, including the spleen, kidney, and suprarenal gland, are uncommon and typically occur after blood spread.

Cutaneous amoebiasis is caused by direct extension around the anus, colostomy site, or discharge from amoebic abscesses. Extensive gangrenous skin damage ensues. The lesion could be confused for condylomata or epithelioma.

Penile amoebiasis, caused by anal intercourse, affects the prepuce and glans. Females may get similar lesions on the vulva, vaginal wall, or cervix, which spread from the perineum. The devastating ulcerative lesions resemble cancer.

Laboratory Diagnosis

Amoebiasis is diagnosed by detecting E.histolytica trophozoites or cysts in feces, tissues, or lesion discharges. Cultures are not used for routine diagnostics. Immunological assays are not effective for diagnosing intestinal infections, but can be useful for extraintestinal amoebiasis.

Intestinal Amoebiasis

Acute amoebic dysentery should not be confused with bacillary dysentery. Collect a feces sample in a wide-mouthed container and analyze it immediately. Antiamoebic medications, bismuth, kaolin, or mineral oil may interfere with trophozoite detection. Examine for macroscopic and microscopic characteristics, and routinely check for additional parasites. It is advised that three distinct samples be examined.

Macroscopic appearance: The stool is semi-liquid, brownish black, and contains foul-smelling feces mixed with blood and mucus. It’s an acidic response. It does not stick to the container.

Microscopic appearance: The cellular exudate is scanty and contains a few pus cells, epithelial cells, and macrophages. The red cells are clustered and appear yellowish or brownish red. Charcot-Leyden crystals are frequently found. However, this discovery is merely suggestive; they may also arise in other bowel illnesses, such as ulcerative colitis and cancer. Active motile trophozoites of E.histolytica can be seen in unstained saline mounts after passing motion that has not been combined with urine or antiseptics.The presence of swallowed erythrocytes confirms the identify of E.histolytica, as they are not seen in any other intestinal amoeba. In acute instances, stained films may not be essential for diagnosis. However, trichrome or iron-haematoxylin stained films offer reliable identification and distinction.

Culture and serology are not commonly used. Serology is often negative in early instances and without profound invasion.

Chronic Amoebiasis and Carriers

Sigmoidoscopy can detect amoebic ulcers in the colon, and biopsy tissue can be obtained for direct microscopy and histology. Identifying asymptomatic carriers is crucial in epidemiological surveys and screening individuals working in food handling jobs.

To detect trophozoites and cysts in chronic patients, convalescents, and carriers, feces may need to be examined after a saline purge, in addition to naturally passing stools. Amoeba excretion is erratic, requiring repeated stool examinations. The demonstration of cysts is made easier by using a proper concentration method, such as the zinc sulphate centrifugal flotation technique. Examination of iodine and iron-haematoxylin-stained preparations is useful. Trophozoites may be in the minuta form and not contain erythrocytes. Differentiation from different amoebae may need the examination of nuclear morphology following staining. Samples can be fixed with 10% formalin, Schaudin’s fixative, or polyvinyl alcohol and stained with Gomorri trichrome or periodic acid Schiff stains.

Cultures are not commonly utilized, but can occasionally provide good results in circumstances when microscopy is negative. Cultures can differentiate pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains based on their zymodeme patterns. Serological testing may only be positive for invasive amoebiasis.

E.histolytica antigens can be identified in clinical samples using immunodetection techniques. ELISA reagents are very specific and can distinguish between E.histolytica and E.dispar antigens. Polyvalent immunochromatographic strip assays identify amoeba, giardia, and cryptosporidium antigens in stool samples.

Extraintestinal (Invasive) Amoebiasis

Diagnosing widespread hepatic amoebiasis (amoebic hepatitis) without localized abscess development might be challenging in the lab. Stool examination is frequently negative for amoebae, and there may be no history of dysentery. Serological testing can be useful in certain circumstances.

Craig (1928) was the first to describe a complement fixation test. Several serological tests have since been developed, including indirect haemagglutination (IHA), latex agglutination (LA), gel diffusion precipitation (GDP), cellulose acetate membrane precipitation (CAP) test, counter current immunoelectrophoresis (CIE), and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. Although lHA and LA are extremely sensitive, they frequently provide false-positive outcomes. They stay positive for several years following effective therapy. Gel precipitation tests are less sensitive but more precise. ELISAs are both sensitive and specific, and, like GDP and CIE, turn negative within six months of effective therapy. Amoeba antigens may be detected in blood pus and feces using very sensitive radioimmunoassays (RIA) and DNA probes, but these methods are too difficult for practical usage. During diagnostic aspiration of a liver abscess, the pus retrieved from the center may not include amoebae, which are limited to the periphery. The fluid that drains after a day or two is more likely to include a trophozoite. Aspirates from the abscess edges would also reveal trophozoites. Extraintestinal lesions do not include cysts.

Other Extraintestinal Amoebiasis

In pulmonary amoebiasis, the trophozoite can be seen in the expectorated anchovy sauce sputum. Cutaneous amoebiasis and other invasive lesions may have visible trophozoites.

Immunity

Invasive strains cause immune responses, with antibodies detected within a week. Infection provides protection, with limited recurrence of invasive colitis and liver abscess. HIV infection doesn’t affect amoebiasis severity, and noninvasive zymodeme infections rarely yield a serological response.

Treatment

Amoebiasis is treated using luminal amoebicides (diloxanide furoate, iodoquinol, paromomycin, tetracycline) and tissue amoebicides (emetine, chloroquine), effective in systemic infection but less in the intestine. Metronidazole and related compounds act at both sites, but emetine’s toxicity has led to its discontinuation.

Prevention and Control

Faecal-oral infections require general prophylaxis, food and water protection, detection and treatment of carriers, and exclusion from food handling occupations. Health education and healthy personal habits also help control the spread of infection.

Conclusion

In summary, we need to know Entamoeba histolytica to understand the public health problems this organism causes. Entamoeba histolytica is responsible for a lot of morbidity through amoebic dysentery and epidemiologically. Knowing its morphology and lifecycle stages is key to diagnosis which is key to treatment and prevention. This will increase awareness and diagnostic capacity of E. histolytica infections and will lead to better management and health outcomes in affected populations. More research and education will be needed to stop this parasite from undermining global health.

1 Comment